How Strong Does the Evidence Need to Be?

All marketers have had to make decisions without complete data. That reality isn’t new, and it isn’t the problem.

The real problem is that most teams don’t agree on how much evidence a decision deserves before action is taken. A creative tweak, a budget reallocation, and a channel expansion are treated as if they should all be judged by the same metrics, on the same timelines, with the same level of confidence.

That’s how attribution gets stretched beyond its limits, incrementality gets misused, and reporting becomes a tool for justification instead of judgment. This article lays out a practical framework for deciding what kind of evidence a decision is allowed to rely on, before measurement begins.

TL;DR

- Marketing decisions should start with decision design, not metrics.

- Every decision has different stakes, reversibility, and scope, which determine how much evidence it deserves.

- Evidence consists of its scope, strength, and cost.

- Most failures come from using evidence to justify conclusions that outlive the evidence itself.

- Strong teams match evidence strength to decision risk to avoid false confidence.

Before Action: Decision Design

Every marketing decision starts with a choice, but most teams skip the most important step: clearly defining what decision is actually being made.

Not all decisions carry the same weight. A creative tweak, a bidding adjustment, or a goal optimization is fundamentally different from expanding into a new channel or reallocating a significant portion of budget. Treating them as equivalent is how teams end up either over-analyzing small changes or under-testing large ones.

Before looking at any metrics, two questions need clear answers:

- What’s at stake if we’re wrong?

- How reversible is this decision?

Stakes are often reduced to money, but financial cost is only one dimension. Decisions also shape organizational belief (what the team thinks “works”), influence strategic direction, and establish future norms. A poorly interpreted channel test can affect decisions long after the spend itself has stopped.

Reversibility is about more than time. It includes operational friction, political cost, and how difficult it will be to walk back a conclusion once it’s been internalized. Some decisions are technically reversible but practically permanent because of how they’re remembered and referenced later.

Once stakes and reversibility are clear, the next question naturally follows: what kind of evidence is actually appropriate for this decision?

Realize that “evidence” is not one thing

Most marketers equate evidence with metrics: clicks, conversions, CPA, lift percentages. Those are inputs, but they aren’t evidence on their own.

At its core, evidence is information that meaningfully reduces uncertainty for a specific decision. And not all evidence does that equally.

Evidence has three properties that matter when evaluating whether it’s fit for purpose:

- Scope

- Strength

- Cost

Scope defines which decisions the evidence is allowed to inform. Signals used for creative iteration are local, affecting only a small part of the system. Evidence used to justify a product positioning shift or channel expansion is strategic, with effects that ripple across the entire organization.

Strength is the weight the evidence carries for the decision at hand, not just statistical significance (e.g. 10% lift, so we must have done great!). Strong evidence holds up under noise, bias, and external interference. It remains directionally consistent across time and context, rather than collapsing under small changes in assumptions or environment.

Cost is often underestimated. Evidence isn’t free. It requires time to collect, patience to interpret, and organizational effort to execute correctly. High-cost evidence should only be required when the cost of being wrong justifies it.

Why More Evidence is Not Always Better

The instinct in marketing is to gather more data to feel more confident. In practice, more evidence often introduces more noise, more bias, and more opportunity for misinterpretation.

Evidence doesn’t exist to eliminate uncertainty – it exists to reduce specific uncertainties enough to act responsibly. The balance between savvy analysis and over-analysis is a fine line.

The goal isn’t more evidence. It’s the right level of evidence for the decision being made.

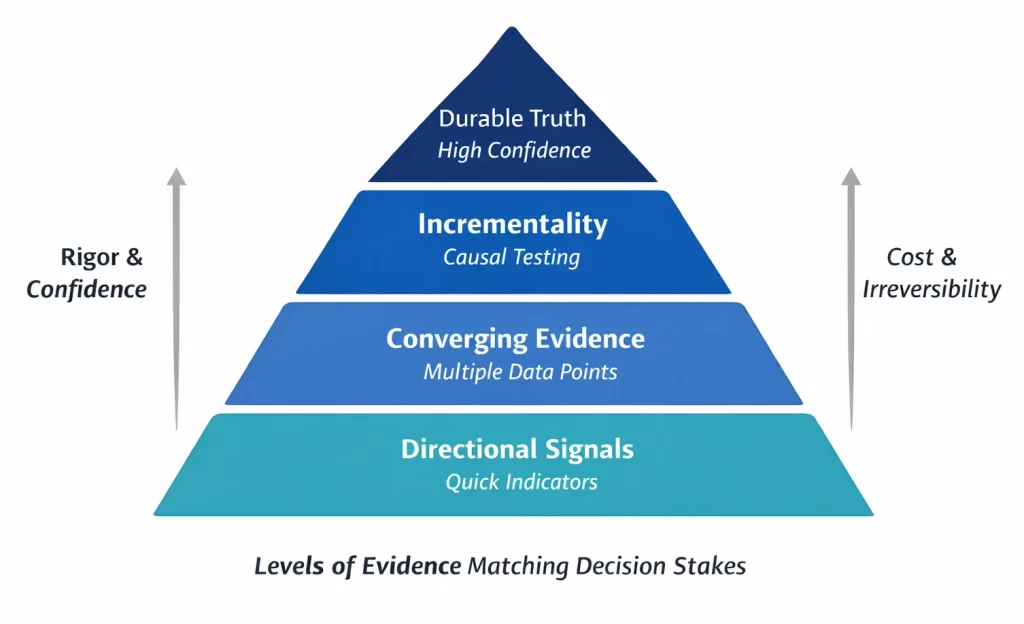

The Confidence Ladder

We’ve looked at a confidence ladder that breaks down evidence into four main categories.

Each level varies on Scope, Strength, and Cost making them useful in different contexts.

Directional Signals

- Scope: Local

- Strength: Low

- Cost: Low

Directional signals are used for small, reversible decisions made within a single system. Creative variations, optimization goals, pacing adjustments, and localized tests fall into this category.

They are not designed to support cross-channel comparisons or strategic conclusions. Differences in attribution windows, media dynamics, and user behavior introduce noise that directional signals cannot resolve.

When teams stretch directional signals beyond their scope, they mistake movement for meaning. Short-term efficiency gains get interpreted as impact, and decisions accumulate confidence faster than understanding.

Converging Evidence

- Scope: System

- Strength: Medium

- Cost: Medium

Converging evidence is used when decisions extend beyond a single platform but remain reversible. It is the minimum requirement for evaluating cross-channel performance and making coordinated optimizations across systems.

Its value comes from repeatability. When independent sources point in the same direction, confidence increases that a pattern is real rather than an artifact of any one system.

Converging evidence doesn’t justify why you’re running a specific channel. Without control over external variables, it cannot reliably separate contribution from coincidence. But it does provide a clearer picture of impact than attribution.

Incrementality

- Scope: Strategy

- Strength: Medium-High

- Cost: Medium-High

Incrementality is the escalation point when a decision cannot responsibly rely on directional or converging signals. It is most appropriate when the outcome will influence future strategy, channel beliefs, or long-term budget norms.

The purpose of incrementality here is protection – when teams guess in these situations, the cost isn’t short-term inefficiency but long-term mislearning.

I’ve written separately about how incrementality tests work and their limitations. In this framework, their role is simply to reduce uncertainty when guessing would be irresponsible.

Durable Truth

- Scope: Governance

- Strength: High

- Cost: High

Durable truth is reserved for decisions that set long-term direction. It informs how marketing systems are governed over time. Think media mix modeling with data from at least the past 2 years.

This level of analysis acts on the highest level of marketing strategy – planning channel mix and budget allocation with a high degree of confidence.

Its strength comes from stability, not responsiveness. When patterns hold across cycles, conditions, and interventions, they become key to shaping strategy.

The risk at this level is false certainty. Because durable evidence carries authority, flawed assumptions or incomplete data can create bad policy. Use it to guide direction, not to resolve short-term debates or explain week-to-week performance.

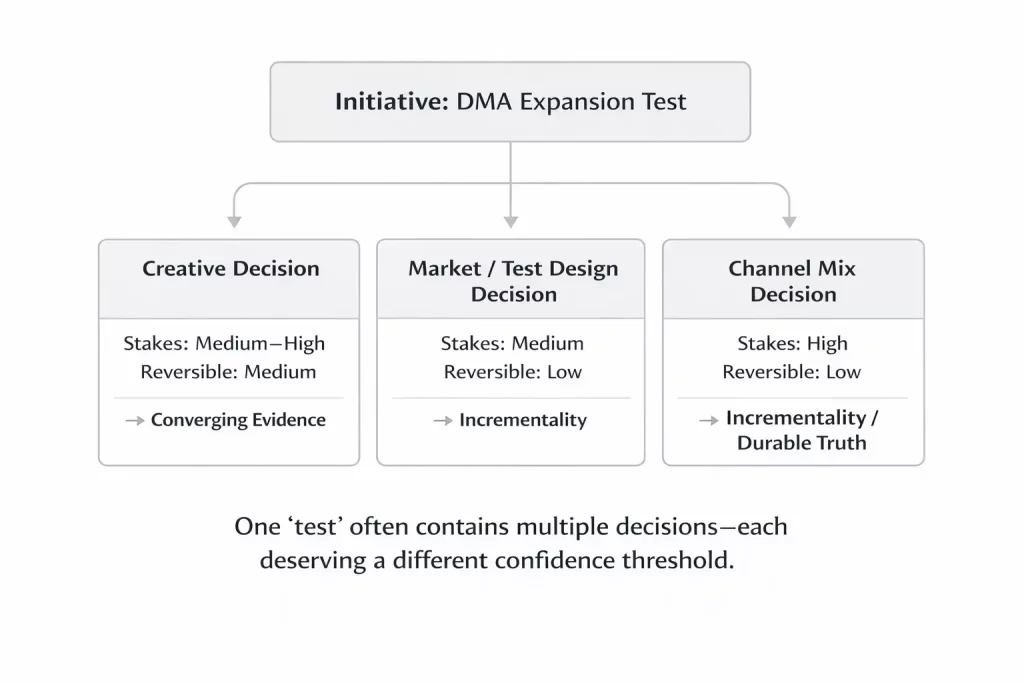

Applying the Framework to a Real Decision

A team decides to run a campaign in a single DMA to test a new creative messaging strategy. To limit risk, they keep it to one market. To improve learning, they expand into new upper-funnel channels alongside their core performance mix.

On paper, this sounds like one decision. In practice, it isn’t.

What looks like a single test campaign is actually several tests layered into one. Each has its own stakes, reversibility, and evidence requirements.

The Creative Question (Often Misclassified)

The first test is creative.

New messaging isn’t as simple as turning an ad on and off. It requires weeks if not months of work, alignment across teams, and strategy for what resonates in market.

Creative that is judged too quickly, or with the wrong evidence, leads to bad optimizations. Worst of all, it can form lasting conclusions about what works (and what doesn’t) and influence future briefs and directions.

This is why directional signals are rarely sufficient alone. Creative decisions need converging evidence over time, even if the execution is reversible.

The Market Question (Where Risk Quietly Increases)

Running the test in a single DMA feels safer than going national, but it introduces a different kind of risk.

Smaller markets are less forgiving. Volume is smaller, external factors are amplified. Running a campaign during an event like say the World Cup could artificially increase CPMs.

Here, the real stake isn’t the incremental spend. It’s how the outcome is interpreted.

Because market tests influence how results are generalized, incrementality becomes necessary. Not to improve campaign results, but to protect learning from being distorted by noise.

The Channel Question (The Most Common Blind Spot)

The final commitment is channel mix.

Testing new channels is an exploratory exercise and carries inherent risk. Channels labeled as ‘winners’ or ‘losers’ rarely get a clean second chance. Attribution is mostly to blame for this.

Teams that treat directional signals or early convergence as proof of performance often draw the wrong conclusions.

Evidence requirements should be set by how definitive the conclusion will be. When a test is intended to assess channel viability, longer timeframes and stronger evidence are needed.

What This Example Shows

It’s a mistake to use the same evidence to judge all three decisions in this test.

Decomposing the decisions exposes which parts require stronger evidence and which do not – something that’s rarely obvious at the outset.

That’s the purpose of the framework: to break decisions apart so evidence isn’t asked to support conclusions it can’t sustain.

Making The Right Decisions

Most marketing mistakes aren’t caused by missing data. They’re caused by asking evidence to do work it was never meant to do.

Attribution isn’t flawed because it’s imprecise. Incrementality isn’t powerful because it’s causal. Reporting doesn’t fail because teams choose the wrong metrics. They’re tools that use evidence to draw conclusions.

Good teams don’t chase certainty. They design decisions so that confidence is earned where it matters. That means defining the decision before measurement begins, understanding what’s truly at stake, and selecting the appropriate evidence.

The goal isn’t to eliminate uncertainty. It’s to prevent false confidence from turning into belief, strategy, and governance.