Why Scaling Too Early Destroys Learnings

You start running a campaign at a low daily budget. It performs well, driving conversions comfortably below your target CPA. Encouraged by the results, you increase spend.

You raise the budget from $100/day to $500/day. Conversions increase by 50%, but total CPA rises by 250%. What was once a strong performer is now bleeding money.

The unspoken truth: this outcome was always likely.

Scaling doesn’t just increase spend. It changes how the system behaves. What worked within a narrow, high-intent audience often can’t support broader reach without structural change.

This happens to almost everyone. The difference is whether teams recognize it as a learning failure, not a performance failure. This article breaks down why scaling destroys learning when understanding doesn’t keep pace, and how to avoid it.

TL;DR

- Early campaign success is driven by constraint, not scalability

- Scaling changes system behavior, not just spend levels

- As complexity increases, attribution signals degrade and learning slows

- Each stage of scale requires a different decision process and evidence focus

- Scaling works when understanding grows faster than budget

The Illusion of Early Success

Most campaigns start small. Budgets are limited, reach is narrow, and spend is intentionally limited until something “works”.

This setup creates a powerful illusion. Early performance often looks exceptional not because the strategy is scalable, but because conditions are unusually favorable:

- Small budgets concentrate spend on high-intent users

- Core audiences are reached first

- Competition is lower within narrow targeting windows

What looks like success is often evidence of constraint, not proof of scalability.

As campaigns expand beyond these favorable conditions, complexity increases. Audience composition shifts, platform behavior changes, and the clean signals that existed early begin to degrade.

Scaling Is a Regime Change, Not a Linear Increase

Scaling is often treated as a simple extension of what already works: increase budget, reach more people, drive more results.

In practice, scaling changes the system you’re measuring. As spend increases, complexity rises in predictable ways:

- Audience composition expands beyond core users

- Platforms shift delivery behavior to maintain efficiency

- Attribution signals become noisier

The audience reached at scale is fundamentally different from the audience reached early. More users are less aware, further from a decision, and exposed across multiple channels. Platforms increasingly overlap in who they reach and compete for credit on the same outcomes.

The result is degraded evidence. Attribution appears more confident as spend grows, but becomes less informative about true impact. Scaling doesn’t just effect performance – it reshapes what your data can reliably tell you.

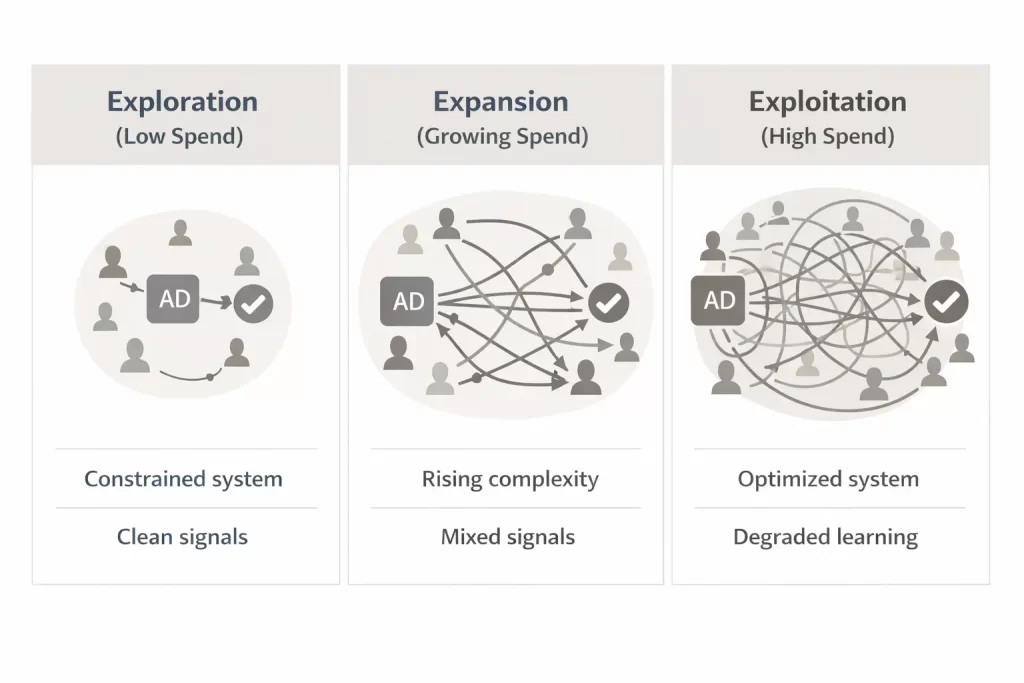

The Three Scaling Phases

Scaling is often synonymous with increase spend, but what’s missed is how it changes the structure of the marketing system. As budgets grow, so does campaign complexity.

Three distinct phases, defined by how learning behaves, explain why the same measurement and decision methods stops working as spend increases.

Note on budget ranges: The spend levels below are illustrative, not prescriptive. Market size, audience depth, and product demand all affect when a campaign enters each phase. Smaller or more constrained markets often reach later stages sooner.

Phase 1: Exploration (~$100/day)

The exploration phase is defined by constraint.

Limited budget, limited reach, and few creatives or messages keep the system relatively simple. Typically, few things are changing at once making cause-and-effect easier to see.

Learnings are abundant in this phase, especially with early creative and audience insights. Fewer variables in play means signals stand out against noise (especially when segmented into tighter market groupings).

Because of this, directional signals are usually sufficient because attribution bias is contained within a single platform and narrow set of tactics.

The tradeoff is time. Volume is low, so meaningful conclusions often require weeks rather than days. This is one of the few stages where it’s truly possible to “learn a lot from a little”, given changes aren’t rushed.

Phase 2: Expansion (~$1,000/day)

Expansion is the first real stress test of the system.

While it’s marked by increased spend, the more important shift is complexity. What previously worked within a narrow, high-intent audience is now extended across more audiences and channels – frequently at the same time.

As complexity increases, learning becomes harder. Overlap in changes make it hard to isolate which change actually drove the impact. Attribution bias and conversion lag, which were manageable in a single channel system, are amplified with multiple channels in the mix.

Directional signals that once felt reliable start to break down. Performance doesn’t move as cleanly in response to individual changes, and conclusions drawn at the channel level become increasingly suspect

At this stage, learning shifts from channel observations to portfolio-level interpretations. Confidence comes from converging evidence across multiple sources though a healthy amount of uncertainty remains.

Expansion doesn’t reduce learning, it just makes them harder to observe.

Phase 3: Exploitation ($5,000+/day)

The exploitation phase begins when the platform stops exploring.

At this scale, algorithms have enough data to establish consistent paths to conversion, and begin prioritizing efficiency over discovery. Spend typically concentrates around patterns that have been proven predictable.

This is where campaigns show how much the system will tolerate.

Incremental dollars reach lower intent users as the high-intent audiences are exhausted. Without meaningful changes to creative, messaging, or structure, performance degrades as the system pushes further outside the core converting audience.

Learning becomes limited. Higher budgets across multiple channels blur the lines of impact further and directional signals lose decision-making value. Attribution appears strongest, but is actually at its least informative.

At this stage, evidence requirements become more rigorous. Understanding impact requires more deliberate methods, because insight no longer emerges naturally from scale.

At exploitation scale, performance data reflects how the system is optimized, not necessarily how customers are individually responding.

How Decision-Making Changes as You Scale

Scaling isn’t just increasing budget, it’s maturing your strategy and tactic mix to support a higher daily spend. Each phase requires an adjustment in how to structure campaigns and use evidence to validate results.

Teams that fail to adjust how they interpret performance data often believe they’re optimizing, when they’re actually misreading the system.

Exploration → Optimize for Learning

This is the only phase where risk is structurally low. Spend is limited, reach is narrow, and the system is simple enough that individual changes still produce visible movement.

At this stage, the goal isn’t to prove a channel works. It’s to surface what might work.

Focus on:

- Maximizing learning per dollar, not efficiency

- Making fewer changes, less often (monthly)

- Measuring with directional signals

Directional attribution works here not because it’s accurate, but because it’s contained within a single system. Set up your campaign and let it run. Don’t over-optimize.

Expansion → Optimize for Signals

Expansion increases complexity. More creative, more offers, more audiences, and often more channels enter the system at once. This looks like adding a lead gen component to a e-commerce business, or a warming sequence for long sales cycles.

What worked in exploration may still work, but it now competes with noise.

Focus on:

- Separating decisions (creative, offer, channel) instead of bundling them

- Looking for converging evidence across multiple data sources

- Evaluating trends (weekly) relative to change events

Performance must be interpreted at the portfolio level, not the channel level. The goal shifts from “what works” to “what scales without breaking the system.

Exploitation → Optimize for Risk

At this point, several tactics should be working. Now it becomes a matter of proving what’s working and how to effectively spend budget among tactics and channels.

Focus on:

- Proving contribution, not just capture

- Incrementality testing to resolve attribution conflicts

- Treating performance plateaus as diagnostic signals

At this stage, performance data reflects how the system is optimized, not necessarily how customers are individually responding. Without stronger evidence, teams risk scaling what looks efficient while eroding true impact.

Scale Should Follow Understanding, Not Lead It

Scale doesn’t fail because platforms are broken. It fails because marketers mistake learning for proof.

Just because one thing happens, doesn’t mean it will continue to happen as the system complexity increases. When spend grows faster than understanding, teams spend more time optimizing than learning.

That’s how learning gets destroyed.

The answer isn’t to avoid scaling. It’s to treat scale as a sequence of strategic shifts, not a single action. Each stage requires its own plan, its own evidence standard, and its own decision process.

When teams adjust how they interpret performance at each stage, scale becomes a source of insight rather than confusion. It doesn’t reveal what works – it confirms what you’ve actually understood well enough to scale.