Why Efficient Campaigns Feel Safer — and Teach You Less

In paid media, efficiency is comforting.

Known audiences. Familiar messaging. Predictable performance. When campaigns behave the way they did last quarter, it feels like control, and control feels responsible.

That instinct isn’t wrong. Efficiency protects you from obvious mistakes. But it comes with a cost that’s easy to miss.

In a media landscape where platforms, algorithms, and buying behavior change constantly, this creates a dangerous trap. The more comfortable your campaigns feel, the less they expand your understanding of what actually drives growth.

This is why many advertising strategies don’t fail loudly. They stall quietly.

Take campaign structure – 5 years ago, a hyper-segmented campaign approach using interest targets and funnel stages would have been the right approach. Today, that has changed considerably with algorithm updates like Meta Andromeda.

This article breaks down why “safe” campaign structures often block learning, how modern ad platforms reinforce this behavior, and where control actually belongs if the goal is long-term performance, not just short-term efficiency.

TL;DR

Efficient campaigns feel safe because they exploit what already works, but that safety comes at the cost of learning. Fragmented structures, retargeting, and hyper-targeted audiences create the illusion of control while starving algorithms of the scale and variance they need to discover new demand. Modern platforms optimize for efficiency by default; learning only happens when marketers make larger, deliberate structural changes. Growth doesn’t stall because campaigns fail. It stalls because nothing new is being tested.

Why Control Feels Productive (and Isn’t)

For years, paid media rewarded control.

Advertisers segmented audiences, separated funnel stages, capped budgets tightly, and isolated performance into neat reporting buckets. Each campaign answered a specific question: Who converted? At what cost?

That structure felt analytical. Insight-driven. Responsible.

But it also created an illusion.

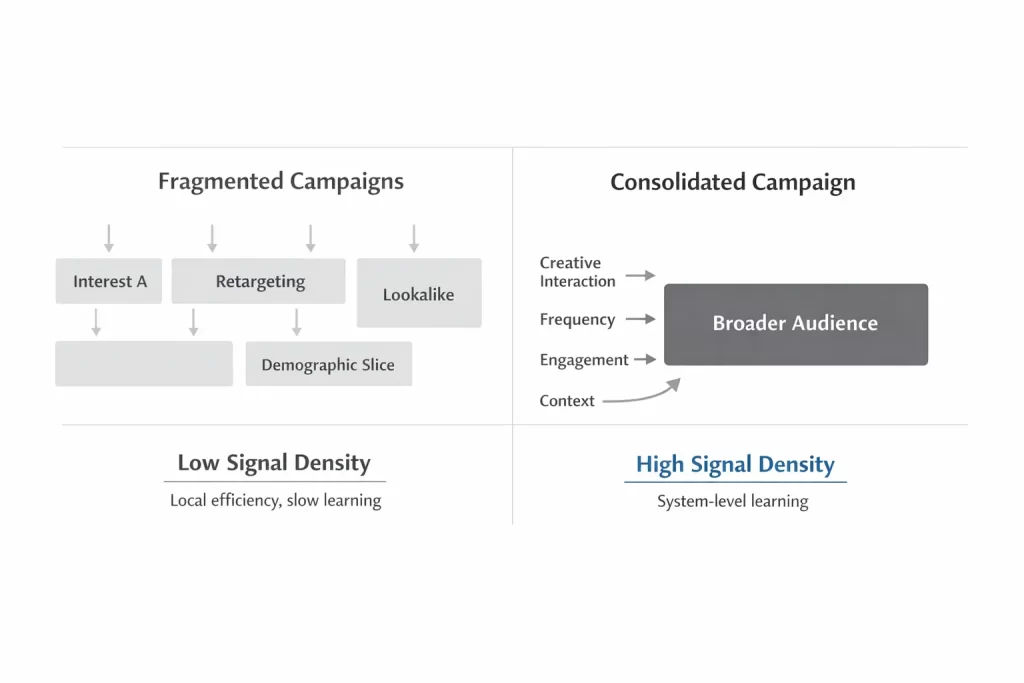

While fragmentation increased visibility at the campaign level, it reduced learning at the system level. Each audience became too small to generate meaningful signal volume, and insights stopped compounding across the account.

The result is a paradox: the more control you apply locally, the less the system learns globally.

Granular structures don’t just slow optimization. They narrow what the algorithm is even allowed to discover.

Why Consolidation Feels Risky (But Unlocks Learning)

Campaign consolidation feels uncomfortable because it removes familiar levers.

When audiences are merged, you lose clean breakouts. Retargeting no longer has its own CPA line. Attribution becomes messier. Reporting feels less precise.

That discomfort is exactly the point.

Consolidation forces the system to decide who is high intent instead of confirming who you already assumed was.

Algorithms don’t think in audience labels or funnel stages. They infer intent from behavior patterns across thousands of signals – frequency, creative interaction, dwell time, sequence, context.

Instead of pretending to know our audience better than an algorithm, the marketers job becomes one of strategic planning.

Creating a campaign structure with the correct optimization goals and geographic targeting and budgeting becomes the primary focus.

Smaller “optimizations” are traded in favor of larger perturbations. Analysis shifts from daily to weekly or monthly.

What this means practically is less focus on high efficiency, and greater focus on system-level performance.

The Hidden Tradeoff: Efficiency vs Learning

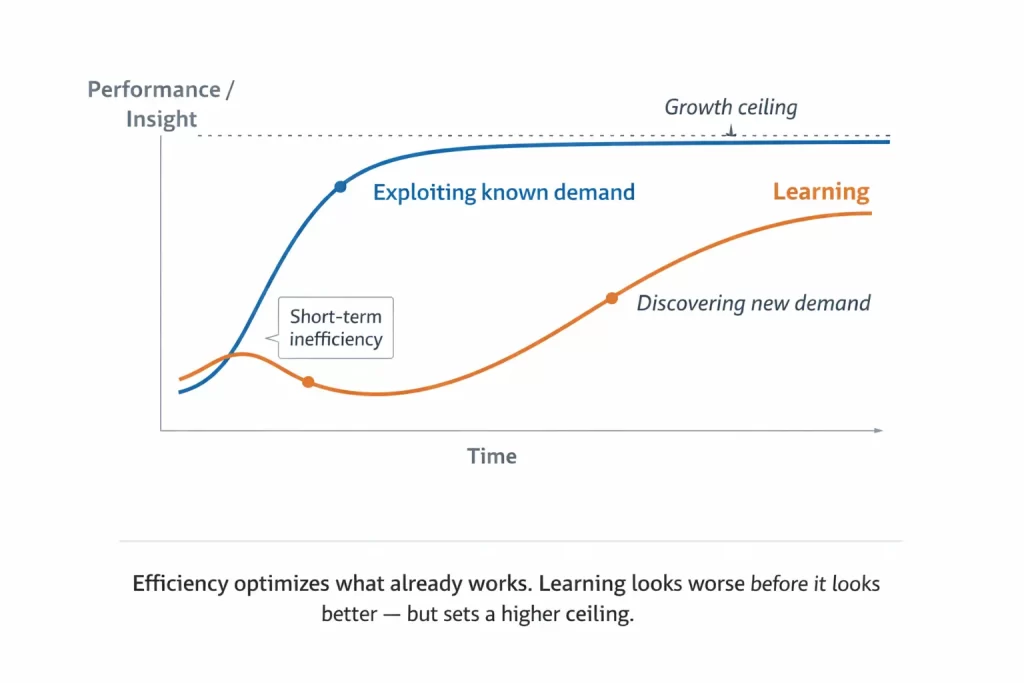

Efficiency is not the same thing as progress.

Efficiency exploits what already works. Learning requires exposure to what doesn’t yet.

In the short term, learning is almost always less efficient. New audiences convert slower. New messaging underperforms initially. Variance increases before results improve.

Modern ad platforms are built to minimize this variance. Their default behavior is to push spend toward the most predictable outcomes as quickly as possible.

Left alone, platforms optimize toward efficiency, not discovery.

Learning only happens when advertisers deliberately disrupt that equilibrium. Through structural changes, creative shifts, or expanded audience scope, you force the system to explore instead of exploit.

This is why highly efficient campaigns often plateau. They are doing exactly what they were trained to do, and nothing more.

Why Efficient Campaigns Are Often the Least Informative

Efficiency is a signal for success because marketing only works when it hits goals. Those goals are often tied to a metric like CPA (not great) or Sales (better).

Because efficient systems are predictable, they’re sought after. Efficient systems aim to minimize variance in results which naturally means they gravitate toward known users.

The Case Against Retargeting

Retargeting has been a core tactic in digital marketing strategy since the birth of the internet. The concept is simple: follow users who have visited your website or engaged with an ad because they are more likely to convert.

This knee-caps learnings because now ads are targeted to a small subset of the total target audience. Usually 1 or 2 ads dominate ad spend and performance holds steady – not great conditions for learning.

Results are healthy, but don’t scale as easily. There’s also a high likelihood that spend is wasted on users that are never going to convert.

The Case Against Branded Search

We’ve reviewed cases where branded search campaigns are not effective. These are also situations where learning is actively hampered.

Targeting users that already know about the brand and likely are going to convert anyway is about as good as looking at first-party data.

Branded search artificially creates efficiency by taking “credit” for conversions that happen anyways, and are one of the biggest culprits in wasted ad spend.

The Case Against Hyper-Targeted Campaigns

Interest and demographic targeting segments are great when there’s a very specific audience that needs to be reached. However, with most campaigns, restricting an audience for the sake of perceived efficiency sacrifices potential.

Often times, these restricted audiences target the warmest audiences (those with the highest intent), which makes efficiency look strong, but limits scale.

To grow, an audience must have a sizable margin of new-to-brand users to introduce the brand and product to prospective customers. Not recycle those who are already aware and considering.

Fragmentation Feels Like Learning (But Isn’t)

Fragmentation feels like it produces better learnings because there are different audience breakouts, more local changes, and comparisons between tactic groupings.

In reality, it fragments an audience so that bias takes over and signals never compound.

Audience makeup often overlaps as well which creates further confusion. Just because an audience is more efficient, doesn’t mean it’s a better candidate for your budget.

Reframing Control: Where It Actually Belongs

Instead of controlling campaigns through fragmentation, marketers mindset needs to shift to system design.

System design involves the inputs needed to create a campaign: creative, offers, audiences, demographics, geography, etc.

Control these variables in a carefully planned strategy, and let them run.

Modern paid media systems are designed to penalize constant tweaks, micromanagements, and daily optimizations.

Instead, decision-making happens on a longer cadence (monthly) with larger, methodical changes.

This mindset shift isn’t easy, but pays off tremendously when implemented correctly.

Comfort Is the Enemy of Insight

Efficient campaigns feel safe because they reduce uncertainty. Fragmented structures, narrow audiences, and familiar tactics give marketers a sense of control and predictable outcomes.

But stability isn’t learning.

As platforms mature, they optimize toward efficiency by default. Small changes get absorbed. Performance can hold steady but new insights disappear.

The mistake most teams make is responding to this stall with more control: tighter targeting, more segmentation, more micro-optimizations. That creates activity, not insight. Learning only resumes with larger structural decisions – meaningful creative shifts and deliberate disruptions to how demand is generated.

In modern paid media, optimization doesn’t fail because campaigns break. It fails because nothing meaningful is being tested anymore.

Stability is comfortable. Learning is what makes growth possible.